†Christology of The Quadrants of the Cross†

Essay #18: Corrective Practice No. 4: Passing Through the Eye of a Needle

As Jesus started on his way, a man ran up to him and fell on his knees before him. “Good teacher,” he asked, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

“Why do you call me good?” Jesus answered. “No one is good—except God alone. You know the commandments: ‘You shall not murder, you shall not commit adultery, you shall not steal, you shall not give false testimony, you shall not defraud, honor your father and mother.’”

“Teacher,” he declared, “all these I have kept since I was a boy.”

Jesus looked at him and loved him. “One thing you lack,” he said. “Go, sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

At this the man’s face fell. He went away sad, because he had great wealth.

Jesus looked around and said to his disciples, “How hard it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of God!”

The disciples were amazed at his words. But Jesus said again, “Children, how hard it is to enter the kingdom of God! It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.”

The disciples were even more amazed, and said to each other, “Who then can be saved?”

Jesus looked at them and said, “With man this is impossible, but not with God; all things are possible with God.”

Then Peter spoke up, “We have left everything to follow you!”

“Truly I tell you,” Jesus replied, “no one who has left home or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or fields for me and the gospel will fail to receive a hundred times as much in this present age: homes, brothers, sisters, mothers, children and fields—along with persecutions—and in the age to come eternal life. But many who are first will be last, and the last first.”

-Mark 10:17-29

Corrective Practice No. 4: Passing Through the Eye of a Needle

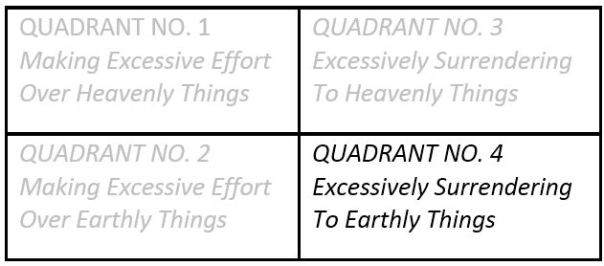

The Gospel

In the previous chapter we observed how making appropriate effort over earthly things–i.e., world work–can be a corrective practice to overmuch surrendering to heavenly things in the form of false discipleship. There is another kind of surrendering, also excessive, which deters one from keeping with Jesus at the center of the cross, and that is excessively surrendering to earthly things. Unlike the corrective practice of doodling in surrender to earthly things, here surrendering to earthly things leads one away from the center of the cross and not towards it.

Excessively surrendering to earthly things is the opposite of the distracting habit of making excessive effort over earthly things we saw in Martha–opposite in the sense that effort and surrender are opposites, although both here refer to earthly things. We might expect, therefore, that making effort over earthly things could, in some sense, be corrective to excessively surrendering to earthly things, and this is true. For example, getting up out of bed and going to work can to some extent be corrective of that lassitude which consists of too much surrendering to the temptations of the bedroom, be they sex, languor, or just plain boredom. However, just as we saw with Martha’s error of making excessive effort over earthly things, the fully corrective practice cannot be found in the opposite of the same genre or domain. Recall that we observed that the error of excessive world work could be corrected, but not fully corrected, by the practice of doodling or by other purely earthbound measures such as collapsing into an arm chair. A full correction required the use of the counter pole not of physical surrender but of spiritual. Here, likewise, the truest counter pole to the sin of excessively surrendering to physical things is not effort of a physical sort but spiritual.

It is important to point out–if it has not already become sufficiently clear–that the corrective practices in each domain can be corrective only if they are embraced as antidotes to the pressure of temptations in the opposite domain. Doodling, for example, is as we said not an end in and of itself but a corrective measure against over-inflated efforts in the spiritual domain. Jesus did not mean it to draw us down to a state of lassitude with regard to earthly things, only to produce enough of a correction in us whereby we could return to him at the center of the cross. Likewise, he did not mean for world work to become for us an end in itself lest it draw us into a preoccupation with earthly outcomes that would totally unseat our souls from keeping company with him at the center of the cross. Rather, in the context of overmuch harboring in a debilitating quasi-spirituality, he meant it to draw us out into a tailwind that could redirect us to him at the center of the cross. Thus, in the present case, spiritual effort is presented not so much as an end in itself but as an antidote to destructive surrender that would keep one from inhabiting the kingdom of God. Once more we observe that sin or error gets defined in the Christology–as do the corrective practices–not abstractly but in the context of the tensions and dynamics that pull us away from Jesus at the center of the cross or restore us to him. The essential character of sin is that it takes us away from God and Jesus, not that it is evil in itself. Likewise, the essential nature of a corrective practice is that it balances de-centering forces or inclinations and therefore restores us to the divine center. Thus what is sin for one person can be corrective for another and vice versa.

As we noted in the last essay, Jesus offered both external and internal frames of reference for our conduct on the Way of Return. We can imagine these arranged like spokes around the hub of a wheel. Taken altogether these frames of reference give us some idea how to comport our lives so as to maintain the integrity of the center. We should indeed take this metaphor to suggest that there needs to be a certain tension present across these spokes, that is, across many of the markers he presents in order for the wheel–and for the center–to retain their shape. For example, Jesus teaches us that “the meek will inherit the earth,” but also “to let your light shine before others.” Again, he teaches us to be “poor in spirit” but also counsels us to “store up for yourselves treasures in heaven.” As we said above, Jesus’s overarching intent is to give us more than specific guidelines to live by. It is to cultivate in us a broad feeling for the tensions and dynamics that pull us away from him at the center of the cross, and can also help to restore us there. If the Christology offered no more than static maxims and directives to be obeyed in our lives, it would be no better than the Law. But Jesus made it clear:

Do not think I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. (Matthew 5:17)

Jesus could fulfill the Law only by offering in place of its static directives the active and living core that alone could make possible his command to us to “be more righteous than the Pharisees and the teachers of the Law.” This core is nothing less than the implicate order of the universe expressed in the Quadrants of the Cross.

Law is just law. It consists of numerous commands and statements that the mind and ego can assent to or not. But the Quadrants of the Cross contains much more. It represents both an ontological and psychological dynamism built into the very fabric of the universe. Therefore it represents both levels of reality–including earthly and heavenly planes–and also varying psychological states from the most illusory to the most enlightened and informed. As we discovered in Essay #7 through the story of Genesis, there is a direct relationship between our state of mind and the ontology we have access to. We encountered this relationship again in our elucidation of the core centering practice in Essay #14. This dynamic relationship is also to be found in the corrective practices of the Quadrants of the Cross.

The mind that assents to a command of the Law does not necessarily become any wiser for doing so. However, the mind that returns to Jesus at the center of the cross through an active discernment of the forces that drew it astray and a participation in the corrective practices that leverage forces that bring it home cannot remain passive and unchanged. That mind has delved into the fabric of its own nature and the fabric of the universe in which it lives. That mind comes to see itself and the whole world as different. Into the new wineskin of its discernment is poured a whole new vision of reality. And likewise, that vision–that ontology–can only exist and be apprehended in the changed state into which that mind has come. Thus the Christology and the Quadrants of the Cross within it were bequeathed to us as the living Way of Return. Through them could Jesus truly say, “The Kingdom of God is at hand.” For they are not a static code or outworn ethics, a set of beliefs or even replicable understandings. They are rather an expression of that fundamental dynamism by which God’s will and our own will can become coherent on this earthly plane. They represent the manner both by which God condescends to meet us here on earth and by which we reach our finger up to be touched by God, to borrow a famous image.

In terms of the ontology we explored in our early writings, the Christology culminates in practices which dispose the very space and time that we inhabit to the opening of God’s cone of excursion. This dynamism is nowhere more clearly to be found in Jesus’s teachings than in the story of the rich young man presented at the start of this chapter. However, it is once again up to us to discover it in the densely esoteric images that Jesus chooses to use. As we already mentioned, the corrective practice presented in this passage is effort applied to heavenly things, and the error this is meant to correct is excessively surrendering to earthly things.

As the story begins, a rich young man suddenly approaches Jesus and prostrates himself before him. He addresses Jesus as “good teacher.” Jesus immediately rejects this salutation and redirects his student to the goodness of God alone. If it seems like we are witnessing here a highly condensed enactment of the error of Quadrant No. 3, that is precisely what this is. The young man would take surrender to Jesus as a remedy, that is, surrender to spiritual things, but his sin is not the same as Martha’s, for which that would be a cure. Martha’s sin was characterized by overmuch effort, but the young man presents from the start as one who is overmuch inclined to surrender. It is clear from the story that he has already accumulated great wealth, whether from his own efforts or those of others we are not told. In any case, it is not effort that binds him; therefore, surrender of any sort–even spiritual–cannot liberate him. Jesus already knows this, and so he quickly rejects the young man’s attempt to surrender to him. Instead, he tests the mettle of the young man’s effort–that which could liberate him–by enumerating the commandments and enabling him to measure his effort against them. This first test the young man is able to pass. “Teacher,” he declared, “all these I have kept since I was a boy.”

Thus we witness what we have just been discussing, the assent of the mind to the commandments of the Law, along with a measure of effort to keep action in accordance. Jesus immediately issues a second test far more reaching than the first:

“One thing you lack,” he said. “Go, sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

At this the young man becomes dejected. His face falls. He goes away sad. The image here is of one collapsing, unable to look upwards, unable to resist the tide coming to sweep him away. The explanation offered is that “he had great wealth.” The tide set against him is that of his own possessions, and the mind state which is his undoing is that of excessive surrender to the things of this world.

At this Jesus turned to his disciples and said:

How hard it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of God!…Children, how hard it is to enter the kingdom of God! It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.

The disciples were amazed at Jesus’s choice of imagery, and we should be also. For they wondered aloud, if the rich with all their wealth and privilege could not enter the kingdom but were actually hindered by these from doing so, then who on earth might have the means to do so? Who on earth could be saved? Jesus’s response seems straightforward on the surface but it is also full of hidden meanings. He tells them:

With man this is impossible, but not with God; all things are possible with God.

On the surface we get the view reflected by Peter, who proclaims, “We have left everything to follow you!” And Jesus in his response makes clear that this is not wrong. Peter is just wondering aloud whether he and the other disciples have actually met the second test that Jesus laid down. Since they did not hold onto their possessions–unlike the young man–did they indeed qualify to enter the kingdom? Jesus assents to his point and reassures him that “no one who has left home or brothers or sisters or mother or father or fields for me and the gospel will fail to receive a hundred times as much in this present age: homes, brothers, sisters, mothers, children and fields–along with persecutions–and in the age to come eternal life.”

We might imagine that Peter and the others would be pleased by this response with the exception of being promised persecutions as well as multiple rewards. But the deeper level of Jesus’s response is far more interesting and revealing. Jesus did not originally answer the disciples’ question “who can be saved?” by saying that they themselves would be saved since they had passed the test of not clinging to possessions. Instead he gave the much more telescopic answer that “with man this is impossible, but not with God.” It was really only when he was pressed by Peter to address the issue of their relinquishing possessions that he conceded to provide the response that Peter wanted. Even so, he quickly qualified it with the still more cryptic verse:

But many who are first will be last, and the last first.

Did we not have Matthew 20:1-16 to explain this verse further, we would be very hard pressed to understand exactly what Jesus meant. Thankfully, we do have those verses. But before we can turn to them, we will need to back up and consider the deeper meaning of what Jesus has been saying up to this point.

Peter, in his own way, was probably content to be told he would enter into the kingdom of heaven for having given up what he owned. Jesus’s deeper response, however, both to Peter and to the other disciples was that it was not really possible for a rich man–or any other man–to be saved by their own design. It was possible for God, but not for man. Had Jesus not made a more conciliatory response to Peter, we could imagine Peter storming off saying: “For what, then, did we make all this sacrifice? To be told that it was impossible for us to do anything to be saved?”

Peter is a lot like us in desperately wanting to find a direct connection between the particulars of our effort as a cause and the resulting outcome of our own salvation. We saw back in Essay #8 how the ego desperately wants to separate God’s particular caring for us from his universal and to link the particular to specific efforts of its own. We also saw that far from guaranteeing us the outcome that we seek, this division affords the ego a false sense of power that actually occludes our sense of God’s universal caring. Whereas God has already made a path for each and every one of us to come home to him, we lose track of that path precisely where we make it our business to carve it out.

Jesus is really offering Peter and the disciples a far more reassuring answer than he gives them the second time, for he is essentially telling them not to worry, that God has their salvation figured out no matter how impossible it may seem to them. It has been part of his universal caring for them and for all mankind from the beginning. Peter wants specifics, and Jesus obliges. But neither the rich man nor the poor is really in charge of his own salvation. God allows them to participate, but God is there unfailingly taking charge when man’s own efforts fail, when his foot stumbles, when he would end up sunken and on the ground again. Sometimes we do indeed fall. Sometimes we hit the ground hard. Sometimes we must. But there is couched in Jesus’s words a hidden promise that God will be there in the end, that nothing is impossible for him.

Looking again at the passage, we find that Jesus says, “It is hard for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.” He does not say it is impossible. He repeats himself and both times he says it is hard. Then he recasts his statement into the famous simile of the camel and the needle. At first glance, this would seem to just add traction to the statement he already made about the difficulties of the rich. It would seem just to make those seem insurmountable. On the surface level, that is how Peter and the others do indeed take it. However, there is a deeper level to the imagery and to the parable of the workers in the vineyard which follows. And it is at this level that the practice emerges which is the antidote to the sin of the rich young man. As we have already suggested, that antidote is to exert greater effort as applied to things spiritual.

In the simile of the camel and the needle, it is on one hand quite ludicrous that a camel should be able to pass through the eye of a needle. If we allow that Jesus may have meant something different by “eye of a needle” than a typical sewing needle, we may begin to get some insight. Some interpreters have seen in this phrase a reference to a particular geological formation, a narrow canyon of sorts located in the desert, through which it may have been possible with great difficulty to get a camel to pass. That would at least reconcile with Jesus’s other statement that it was hard–but not impossible–for a rich man to enter the kingdom. If we follow this clue, then what exactly was Jesus telling us about the difficulties of the rich man, and the rich young man who greeted him in particular?

That man, we recall, was unable to let go of his possessions. His effort could not rise above the level of rote obedience to the commandments of the Law. In the simile of the camel, Jesus is asking for something more. He is asking the young man to exert effort precisely where it is hard for him, not where it is easy. He tells him to sell his possessions, to give them to the poor, and to come follow Jesus himself. This level of effort we might observe is entirely different from the relatively comfortable effort the young man had become accustomed to exerting for years in obeying the commandments. It is different because it demands not only a change in behavior but a radical change in both mind state and ontology. We notice that Jesus does not merely tell the young man to go and sell his possessions and give to the poor. He tells him quite specifically to do those things in the context of coming to follow him. In other words, he tells him to exert an uncomfortable level of effort in order to bring himself to the limit border of his current world view. His current view is that he cannot do without his wealth and possessions. This is where his excessive surrender has entrapped him. Jesus is instructing him that he must push himself to the very edge of this view by giving things up and by seeking instead the ontology that sees God as the “Maker of heaven and earth.” Jesus is not really instructing the rich young man to take a horrible loss. By the mind state of his current world view, however, that is exactly how it comes across. Rather, as Jesus says, he is offering him a different treasure, a treasure which it takes a very different mind state to perceive, but a treasure nonetheless. And it is clear from what Jesus says elsewhere that he means it to be a far superior treasure than the man has already managed to accumulate.

The message here for all of us is that God does indeed grant that our own spiritual efforts can and do have the power at least to dispose us towards his grace. Insofar as many of us are surrendered to the attachments we have formed to the physical comforts and benefits we already own, we are much like the rich young man, and can take the practice Jesus is suggesting as an antidote to our sin. A camel, we know, is a very irritable and disagreeable beast. Its stubbornness is legendary. It frowns and spits and can dig in its hoofs. Perhaps Jesus chose it as a good metaphor for our egoic minds. Neither the mind nor the camel wants to press against the eye of the needle. From the viewpoint of comfort, it looks like a perilous journey. Why struggle against the rocky walls of a narrow canyon rather than rest in lassitude at the oasis of physical contentment? Our egos would convince us that we can bivouac ourselves indefinitely against the sands of time, against any shifts in fortune. However, Jesus knew better and counseled that no earthly treasure could withstand the advance of rust and of thieves. The problem with the earthly bivouac is that it is precisely the opposite of what it seems. It seems strong, but it is not. It seems comfortable but its comfort cannot outlast its strength which is waning from the first day to the last.

The answer Jesus gives is to take up the journey. The camel may be stubborn but it can be tamed. In fact, it can be ideally suited for transportation through the desert because it stores water in its humps. The hidden hope here is that even our egos have qualities we can draw on to get us through the tough times. We need to remember that the ultimate shepherd is God himself. As we press on through the canyon that leads to himself, he is never very far away. In fact, his hand is guiding, his invisible hand is leading.

Applying the Practice

To further come to terms with the practice of passing through the eye of a needle, it will assist us to consider the ancient Chinese practice of qigong.

Qigong is part exercise and part the art of movement. The word qi means “power” or “energy,” and the word gong means “discipline” or “work.” Qigong differs from mere exercise because it is movement that is designed to harness energy and not merely to expend it. The key ways in which qigong harnesses energy are through the techniques of “pressing on qi” and “showering qi.” In showering qi one imagines that there are waterfalls and oceans of qi energy all around one. Specific movements are designed to gather this qi and shower it onto ourselves in ways that fill us and replenish us. This is not difficult to understand. More elusive is the technique of pressing on qi. This devolves more from the gong part of qigong, from the discipline or effort involved.

In pressing on qi, one becomes aware of the resistance of the qi around her. If she practices without feeling this resistance, her form becomes sloppy, and she is unable to gather much energy to shower upon herself. If she maintains contact with the resistance and continues to feel it, then she gathers and strengthens the qi within and without. This is called “practicing with sincerity.” Qigong needs to be done with sincerity–with effort–if it is to pay dividends. In a very real sense, we have to do it so that we come face to face with the resistance which makes it hard. We have to find this place of resistance and press into it–press into the qi. The paradox is that by pressing into this resistance we actually gather strength; we gather qi.

Looking more closely at the movements of qigong, we discover that this determination–this pressing on qi–is balanced by yielding. We observe, for example, that while we remain strongly rooted below–in our legs and feet–there is gracefulness and yielding in our movements above. In Chinese terms, we could say that we manifest yang below and yin above, in balance. This is actually a precise re-expression of the ontology presented in the Kabbalistic Trigram and the balance reflected in it between effort and surrender that fosters our strength.

What is significant for us here in regard to the practice of passing through the eye of a needle is the technique of pressing on qi to gather strength. It affords us insight into just what is required of us and what occurs as we exert effort and press against the eye of the needle as Jesus seemed to encourage. For one thing, the example from qigong instructs us to pay close attention in every challenging situation to the interface with resistance that we are inclined to run away from, to distract ourselves from, and to forget as soon as possible. We are precisely instructed by qigong to press on it rather than recoil from it. In a quite similar manner did Jesus instruct the rich young man to lean into the thing which was most difficult for him, that is, to follow him and relinquish his hold on material wealth. Furthermore, qigong tells us that our strength to move through the difficulty lies precisely at that interface. Jesus, too, specifically foretold that the young man–should he persist–would come upon far greater treasure than he had left behind. He would not have told a poor man to sell his personal possessions in order to follow him. Rather he gave that prescription to the rich man because it precisely defined the interface with resistance to spiritual transformation against which that man needed to exert effort in order to change. Pressing against that interface–that needle–was the “one thing he lacked.”

The very question of how such pressure accrues us strength or treasure begs further examination and is not beyond our ability to answer. In fact, what Jesus said in the Lord’s Prayer already addressed it. For as we saw in Essay #14, the prayer for daily bread is a prayer which draws us back from macro or global ruminations about our troubles. It encourages us to interface with God on the much narrower, micro level of our daily needs, and to lean into him and trust him to provide them. “Therefore do not worry about tomorrow,” Jesus tells us, “for tomorrow will worry about itself” (Matthew 6:34). Worry, in general, he strongly discourages as ineffectual (Matthew 6:27), and he further implies that the more global are our worries, the more disconnected they become from present time. We may note that it is at the macro or global level that our worries tend to be inflated with imaginary bad outcomes and fears, as well as negative assessments of ourselves and our abilities to succeed. Here we also find delusions of grandeur regarding outcomes and supercilious self-assessments. In both cases we become weaker just for having lost contact with the reality and truth of the present moment.

Narrower concerns over such things as food and clothing tend not to afford room for the grander ruminations of the ego, partly because they are much more firmly anchored in present time. For the same reason, they keep us much closer to our source of strength. Jesus encourages us to pay attention to our interface with God at this level and to begin by leaning into him for our basic needs. Again, the example of qigong can help us see that we are really only able to influence what is in front of us in the present moment. The only qi that we can touch is that which we can press on directly around us. Likewise, we cannot really address any need or difficulty at a macro level, only on a micro level in present time. From there our influence ripples outward in ever widening circles that are farther and farther removed from our control. The insight that we are not really allowed to know the outcome of our efforts at the macro level promotes yielding and surrender while it hones and limits our present effort into a finer force. We do better when we commit to do the best we can right now and then let go.

It may help to reflect that there are few, if any, problems or challenges we are capable of staying at interface with 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. By dint of that fact alone, we are incapable of exerting complete control over anything. Instead, by pressing against our immediate challenges while yielding to the reality that we are not capable of exercising complete control by doing so, we both exert effort the only place we really can and yield and surrender to God’s higher will, which alone controls and determines outcomes. Here we enter into a new kind of being and doing. We could call it “the Way of Qigong.” Whatever we call it, it is a living expression of the Kabbalistic Trigram. Like Jesus’s challenge to the rich young man, it continually points us beyond our comfort zone. Our comfort zone is tucked away from the interface with challenge and transformation. It is shrunk back to the remove of our ruminations about our problems at the macro level, which is not where we can deal with them. Our comfort zone is therefore really a place of much less power, much less qi, than the interface with our immediate difficulties. Thus the interface and not our comfort zone is the zone of our true power.

At the same time, let us say it again, because the present interface is not at the macro level, it is freed from the worries that go along with a false sense of power. Thus the interface is also a filter checking and limiting the ego’s false claims of power, effectiveness, and control. It is actually a place of yielding where there is ample room for the universe to come to our aid, where God’s true power can enter in and be our help. Jesus is not issuing a prohibition against any planning or thinking about the future. There are many places where he encourages forethought and planning. Rather he is grounding all such considerations in moment to moment contact with the Father, for it is at that interface that we both draw from his power and come to any discernment at all about our very next step. Said another way, if we stay in contact with God’s eternal present–which is all we really have and all we need–then our future is assured. However, if we attempt to control the present fully by working backwards from the preferences for a future that our ego defines, we will have actually have lost contact with that “one thing needed” to guide our way.

We can apply the foregoing to the image of the camel pressing through the eye of the needle to draw out its metaphysics in still greater detail. The passageway of the needle is like the tight space or difficulty we need to press against in order to gather strength. This pressing against difficulty–this pressing on qi–can have an effect on the local space-time continuum in which we find ourselves. As we suggested earlier, this practice of the Christology and the others with it–practices we could also describe as the Way of Qigong or the Way of Kabbalah–can beckon the eye of the needle to open. As such they can invite a cone of excursion to open to us from the Divine, a portal through which to receive help and to access a new mind state, a new view of the universe, and new treasure.

After all this, we can see that the kind of effort Jesus called the rich young man to was not just any effort. It was effort made under the clear intention to follow him. And it was effort which had yielding or surrender hidden secretly within it. That much we have explored in detail. That it was effort which put him in contact with a covetous mind state and a materialistic world view which resisted change, we still need to explore further. For these were at the heart of his surrender to earthly things, which constitutes the sin of Quadrant No. 4. It is to these we now turn as we examine Jesus’s specific teachings through the parable of the workers in the vineyard in Matthew 20:1-16.

We have already observed that Peter clearly wanted to be among the first to enter into the kingdom of heaven. But Jesus warned him:

Many who are first will be last, and many who are last will be first.

He went on to tell the parable about a landowner who went out early in the morning and hired whatever workers he found to work in his vineyard. He offered them the day wage of a denarius. He went to the marketplace again at nine, then again at noon, three, and five o’clock. Each time he hired all the laborers he found. When evening came, he told his foreman to pay all the workers, but the last got paid first and all were paid the same wage of a denarius. Those who worked the full day became angry. They complained that the last “were made equal to us who have borne the burden of the work and the heat of the day.” But the landowner did not draw back. Instead he told them that he was not being at all unfair:

“Don’t I have the right to do what I want with my own money?” he said. “Or are you envious because I am generous?”

In the context of a world view where effort is measured and rewarded proportionately with capital, then capital like effort is seen to be of limited supply, and both are coveted. The possessions and creature comforts that capital affords are coveted alike, whether or not they are the product of any personal effort or just inherited. For the mere threat of having to put out the effort to replace them makes them seem prized and all the more worth surrendering to in this world view. Thus the rich young man could not bring himself to part with them. And even Peter and the disciples who had parted with them wanted guaranteed to them some recompense, some measurable compensation purchased with their sacrifice.

Ultimately under this world view, space and time themselves are taken as limited commodities in a closed system. Interacting with them is like moving puzzle pieces on the surface of a flat game board. The number of pieces is limited and the places they can occupy predefined. Under such constraints our overarching goal becomes to accumulate as many such pieces as we can, or similarly, to arrange the pieces we have accumulated as a kind of armor or hedge against the threat of dissolute living or even death represented by the empty side of the game board. From such a view come maxims like “time is money” and “the bigger the better,” expressions of the capitalization and purely material understanding of time and space themselves.

The world described by Jesus’s parable is not like this, however. It is not a world where God marks our iniquities and rewards us strictly according to the measure of our efforts and accomplishments. Rather, he accepts little and rewards much. By his grace he frees us from having to be perfect in order to receive him. Instead he meets us in our limited and imperfect state and answers even our most paltry efforts with grace upon grace. Those who work in his field for even an hour may be assured salvation alike with those who toil for a day. In this world space and time are not compressed into game pieces on a board flattened by a mind state which can only operate according to the rules of materialism. Instead they rise up off the game board crossing boundaries where the rules of materialism do not apply at all. This is where the practice of pressing on qi–exerting effort upon challenge and leaning into change, as it were–completely eludes the materialist. For it is here where space and time rise up towards oneness and eternity and strength accrues to us and things become possible which cannot be accounted for by our own efforts and certainly not in a closed system.

The practice of passing through the eye of the needle, then, is not the impossible practice of passing with one’s wealth through an impenetrable portal. It is rather the corrective effort with which one addresses his attachment to material goods or to any attachment to earthly life. It is the posture of standing at the interface where effort meets the resistance of exchanging an old world view for a new. It is both the pressing towards the new and the yielding which makes room for it to enter. Here we lean into the place that represents our spiritual growth. The interface with this challenge is the limit border of the materialistic world view that keeps us from realizing God more fully. Here we lean outward and maintain both dedication to the intentions of God’s kingdom and trust in his universal caring and grace. This is likewise a border we press against and a portal into a fuller realization of God, a fuller inhabiting of his kingdom.

At this juncture, as we said, God’s cone of excursion now and again opens. His passageway meets us leading to new life. We lean into the narrow passageway in trusting expectation that the Father grabs the strands of our hair from the other side, grabs and gently pulls as we are born again into a new world and a new life by the power of his Holy Spirit.

There is no one way for us to do this practice. For some, it will indeed mean selling possessions and giving to the poor. For others, it will mean a change of profession allowing the focus of their effort to become less material and more spiritual. This practice can lead to sweeping changes or to incremental changes made over time. And it can lead through a host of unpredictable runs and stitches as new and unforeseen possibilities arise. Here the simile of the needle can be helpful yet again. For a needle also implies the making of a garment. Put in too much effort in one place and the fabric knots up and becomes inflexible–too many stitches. Put in too little effort in another and the garment turns out threadbare and too weak to stand up to living in it. Thus both the art of the needle and the spiritual practice we are describing are learned as we go. The miracle of the finished garment is that all our individual stitches become elevated into something we can actually wear. Likewise, the heart of the practice is to come to trust that God will elevate our efforts toward the spiritual domain so as to satisfy all our needs, including even the material.

The effort called for here is not the unbridled effort that leads to knots. (That would actually overshoot the center of the cross and land us in Quadrant No. 1.) Rather it remains

yoked to God and yielding to his most subtle influence. It is not so weak and flaccid that it constantly rends but rather has the tensile strength–the sincerity–to keep us at the place where God can touch us. Ultimately, this kind of effort bears surrender within it. It brings us to the place where dedication and trust are balanced under the aspiration to know God, the place best described by that most liberating command:

Be still and know that I am God. (Psalm 46:10)

In comparison to the corrective practice of Quadrant No. 3 of building one’s house on rock, this practice alike involves the remedial use of effort. But whereas the former practice used effort in the world as a refining tool for an already spiritual inclination, this practice seeks to elevate one from the lesser inclination of materialism to the spiritual. In that sense, then, this is a more difficult practice just as the practice of sitting at the feet of the master was shown to be more difficult than doodling because the surrender of the former practice called for a transition to a higher realm of being.

Finally, what we have learned about the application of effort here in Quadrant No. 4 applies equally in Quadrant No. 3. Whether our effort is applied to things spiritual in following Jesus or to earthly things in doing world work, our goal is ultimately the same: to act from that place where we dwell with the Father. Thus to build on his rock and to press into the eye of his needle are ultimately metaphors for the same thing. Indeed, at the center of the cross, all corrective practices become one and the same. When unbalancing tensions and dynamics are resolved it ceases to matter how we got to the center. As we said in Essay #9 pertaining to the divine healing of our wounds, the past is, in a way, forgotten and we are truly transformed. As important as they are in their specificity along the journey, from the vantage point of the center the corrective practices all appear like ladders that got us there–more alike than different–and all equally able to be set aside. Even the center itself ultimately disappears or ceases to be needed as a concept separate from God. When one enters into God at the center, one ceases to be of this world, and although in it he is freed from striving as well as from the distinctions that define the Quadrants of the Cross. This is something we will need to explore more fully in the next essay.