†Christology of The Quadrants of the Cross†

Essay #15: Corrective Practice No. 1: Doodling in the Sand

The teachers of the law and the Pharisees brought in a woman caught in adultery. They made her stand before the group and said to Jesus, “Teacher, this woman was caught in the act of adultery. In the Law Moses commanded us to stone such women. Now what do you say?” They were using this question as a trap, in order to have a basis for accusing him. But Jesus bent down and started to write on the ground with his finger. When they kept on questioning him, he straightened up and said to them, “If any one of you is without sin, let him be the first to throw a stone at her.” Again he stooped down and wrote on the ground. At this, those who heard began to go away one at a time, the older ones first, until only Jesus was left, with the woman still standing there. -John 8:1-9 (NIV)

Corrective Practice No. 1: Doodling in the Sand

We will now continue our study of the Quadrants of the Cross by taking examples of practices Jesus taught to rectify sin or “detuning from the Godhead” as it occurs in each of the four quadrants. With the Lord’s Prayer firmly established as God’s tuning frequency or homing beacon, Jesus offered these additional practices as corrections or balances to specific types of drift from the Godhead. We will first consider one practice Jesus taught for each quadrant. Later we will reflect collectively on these examples culminating in a study of Jesus’s teaching at the Well of Jacob. This will deepen our comprehension of the Christology as a methodology for practice and prepare us for a still closer look at its operation upon a variety of difficulties found in everyday life. Our ongoing goal is to come to an appreciation of the Christology both as a profound cosmological and ontological elucidation and as a thoroughly practical guide for realizing the Kingdom on earth.

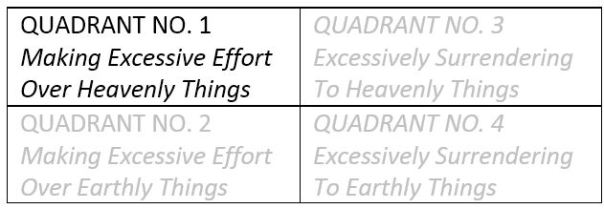

For each practice we consider, we will provide a grid such as the one above showing to which quadrant or quadrants it applies and what error it corrects. We will reference and discuss the Gospel where the practice is taught. Then we will reflect further on the application of the practice.

The Gospel

In the case of the practice of doodling in the sand, we are allowed to witness a most fascinating and instructive scene. The Pharisees have brought an adulterous woman before Jesus and are prepared to stone her in his sight. The situation is volatile, to say the least. Not only do the Pharisees wish to entrap Jesus, they want to commit murder. Thus they are exerting a tremendous effort not only to place themselves in judgment over life and death but to become judges of the Son of God himself.

The Pharisees invoked the Law of Moses as a higher authority commanding them; yet the outcome of this incident clearly demonstrates that they had become seduced and intoxicated over the Law rather than truly commanded by it. If the Law had true authority for them, they would not merely have disbanded under Jesus’s challenge. They would have stood firm, for the Law as they saw it was firm. What changed in the face of Jesus’s challenge was their internal willful resolve. Their will softened. Their untoward effort dissolved.

What was it that Jesus said and did that accomplished this?

By his words he challenged the strength of their will. And by his actions, he demonstrated a practice which served to counteract the excess of effort he was met with. The Pharisees were about making themselves into spiritual prototypes alternative to God, therefore able to pronounce judgments both over life and death and over the Son himself. Jesus ably pointed them inwards and asked them how well they had done applying that faculty of judgment to themselves. And, also, he simply doodled.1

Jesus’s doodling in the sand was like discharging a lightning bolt to ground. For what is the opposite pole to inflated efforts and claims over heavenly things if not surrender to the very dust of the earth by doodling therein? With his question, Jesus exposed the hollowness of the Pharisee’s efforts to become gods. For gods made in the image of the One True God do not impose a power on others which has no root, no anchor within themselves. Moreover, as Jesus often taught, the root of true power is compassion and forgiveness, not harshness and bluster. Jesus’s simple question both exposed the hollowness of their claim to power and put them before their own need for the forgiveness of their sins. Against this, his doodling skillfully illustrated the corrective practice of surrender by coming literally back down to earth and dabbling effortlessly with the grains of sand.

Applying the Practice

Most of us have probably seen examples of the “portable Zen garden,” a tiny sandbox with a miniature rake set into it often found in the waiting rooms of practitioners of Oriental medicine. It’s meant for us to play with. The idea is to use the rake (instead of our finger) to doodle and draw lines in the sand. The inventors say it helps with “letting go.”

The character of sin in the First Quadrant is the polar opposite of letting go. Rather our ego clings to the application of our own effort and very likely also to the outcomes thereof. Furthermore, the subject or focus of our effort is spiritual or quasi-spiritual. The nature of our sin, in sum, is attachment to effort in the heavenly domain.

In learning to apply the practice of doodling in the sand, it will be helpful to make a few further distinctions regarding the particulars of our attachment. Attachment to effort may be strengthened by outcomes, if those outcomes are perceived to be positive. If I exert myself, say, for the spiritual good of another and that other seems to do well and to thrive, there is no doubt a correlation between my effort and their thriving. But there is also the temptation to believe that my exertion of effort on their behalf caused their thriving. This is actually a common mistake in logic, as we observed in Essay #7, because correlation does not imply causation. However, as we also saw, emotional intelligence is often illogical in its findings and in this example prefers once again to inflate the ego rather than give reason its due. In the case of the Pharisees, their logic contained a similar flaw. They believed that if they acted so as to murder the adulteress, they would be glorified by fulfilling the Law. However, Jesus nimbly countered that such an act would leave the Law still unfulfilled because they could not claim to have eliminated all violations within themselves. In essence, he pointed out that they could not close the gap between their own effort and the outcome they intended. The ego always depends on a kind of trumped up isolation from the truth when making its claims in order to keep itself inflated and important. Hence, Jesus could rely on the truth itself to expose that isolation and begin to deflate the ego from its position. His doodling in the sand then became a tour de force demonstration of a completely deflated ego: a man sitting on the ground brushing grains of sand back and forth with his finger.

The reason this practice actually works and has an antidotal effect upon an ego attached to its own lofty efforts is that it conjures several truths in the midst of illusion. It reminds us that we came from dust and shall return to dust, and so serves as a contradiction to too lofty standards and expectations. It replaces the harshness of judgment with the softness of sand. Doodling also is the epitome of loafing and so contradicts our careful measure of our actions and our constricted sense of time. And it affirms in a casual and playful way that human life must always unfold in a setting of uncertainty, unpredictability, and an inability to recreate events exactly. He who draws in the sand even takes delight and finds relief in the randomness of it all. This is, after all, why it is called “doodling.” And it couldn’t be more unlike the driven obsessiveness of the one who takes his own efforts to be precise, essential, effective, and replicable.

It is not that Jesus doodles to recommend it as an act in itself, harmless though it is. We never observe him doodle again. Rather, he offers it at just that moment as a counter pole to what is before him. Like an electronic engineer working with a charge that is too positive, he produces a negative charge to balance it out and bring it to neutral. This is the key point of the practice. When we identify the same type of excess in ourselves, we can apply this practice to bring us back to the center, to return us to Jesus. It may, in fact, help to visualize Jesus before us doodling and encouraging us to doodle with him. And we can bring a variety of scriptures to bear, helping us to remember what rebalancing is all about and where we have gone astray in our journey:

Trust in the Lord with all your heart and lean not on your own understanding; in all your ways acknowledge him, and he will make your paths straight. Proverbs 3:5-6

But as many as received the Light, to them it gave the power to become children of God, to those who believe in its name: who were born, not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man, but of God. John 1:12-13

But seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well. Matthew 6:33

For who makes you different from anyone else? What do you have that you did not receive? And if you did receive it, why do you boast as though you did not? 1 Corinthians 4:7

The final verse, in particular, offers a direct challenge to our assumption that we, by our own efforts, can accomplish anything at all in isolation from that upon which our power depends. Our power ultimately depends on God, and all centering practices rightfully aim at restoring us to Him. That is why Jesus exhorts us to seek first for Him and his kingdom, and says everything else will issue from this. We miss the mark just when we drift from the center of the cross and believe that we must aim directly for the periphery if we are to get what we want. The art of living the way of Jesus is to understand the more subtle balance implicate in the order of the universe. It is to discern in the very cosmology—the rungs of the universe—a resonance and harmony that beckons us back to center. And it is to learn to act in such a way as to replicate and maintain that harmony in oneself as a guide at all times and in all circumstances. The threats of the Pharisees must have sounded freakish and loud, but Jesus kept focus on another strain from another place—a well deep within himself. The source of that well was not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man, but of God.

Thus, we must give up our own will and understanding in order to attain what we want; we must lose our life in order to find it. The path of unsurrendered effort that would seem to lead straight to our goal becomes a very crooked and tortured path. The path of acknowledging God in all ways, including by surrendering our efforts to Him, can seem very crooked and indirect to our addictive egos, but is made straight by the response He makes to our call.

Undertaken with these distinctions, and with the intention to return to Him, the practice of doodling can become a legitimate and helpful spiritual practice. We can doodle about the particulars of our efforts, about who we thought we were becoming, and about what we thought we had achieved. Through the very act of doodling, we can re-inject humor and spaciousness into the stress and tight places created by overmuch self-reliance. We can re-imagine possibilities we had forgotten or shoved aside. We can reconnect with simple delight in the gift of life and the gift of nature. And we can begin to let go of our distorted sense of time and urgency. Doodling itself makes light of the past and future and can seem to exist only in the present. In that way it is a good reminder that God himself dwells in an eternal present both effortless and full of all possibilities.

Ultimately, we do not need a Zen Garden nor even a patch of sand nor a paper tablet to doodle. We can doodle on the tablet of our mind’s eye. We can scribble upon pages written in our hearts. When the body of those pages is filled too full with recountings of our own lofty efforts and with weighty forecasts for more of the same, we can set down in the margins. We can let our finger dance and weave around all those heavy words transmuting their leaden weight into the gold illumination that reflects into our world from another dimension and a higher Source. Thus we can subsume the book that we would write and the outcomes that we would choose into the finer designs and the higher will of God’s Book of Life. Just as the finger is a small part of ourselves obedient to our greater will, so must we come to see ourselves in all of our actions as a small part of God’s body obedient to his will in fulfillment of a much larger plan. And just as the finger is selfless in the performance of its actions, we, too, can surrender ourselves–our egos and our bodies as well–even as we act to fulfill his will. Viewed in this manner, the practice of doodling is elevated to a spiritual practice we can use to return to and to remain at the Jesus point on the cross. Once again the esoteric way is to find the most in the least. In an almost insignificant detail in John’s story is contained this profound way that Jesus gives us to return to him and abide with him on the cross.

Notes:

- John 8:6 strictly says that “Jesus was writing into the earth with his finger.” However, some manuscripts have an additional phrase, translated “as though he heard them not.” Although this phrase may be an interpolation on the part of copyists or scribes, it correctly reflects the tradition current at that time in the East of ignoring someone by turning away and scribbling in such a manner. Had the content of Jesus’s scribbling been important, it surely would have been noted and preserved in this passage. Rather, it is not as writing that Jesus’s scribbling mattered but, as we shall presently see, as a practice of correction and rebalancing. Therefore, it may best be regarded in itself as doodling so as not to find its efficacy in its content but rather in its larger gesture.